Cooperatives, Associations, Mutualities: The Beginnings of Social Economy in Portugal, with Jordi Estivill (Catalonia)

May 7, 2019, 21:30 | Gato Vadio, Porto

Through the analysis of a nineteenth-century magazine from Porto, the Catalan sociologist and economist Jordi Estivill unveils the beginnings of the social economy in Portugal, providing some clues that help to understand past and present developments. The historical documents show signs of “a critical aproach to mainstream political economy, proposals on the reform of measures and institutions of social welfare, and the expression of the workers organisations such as cooperatives, mutual aid societies, and other associations”

Jordi Estivill is a sociologist and economist. Author of numerous books on social and solidarity economy, he is a retired Professor of Social Policy at the University of Barcelona, and one of the founders of the Solidarity Economy Network of Catalonia (XES).

The publication of an article by Jordi Estivill in the Journal of Sociology of the University of Porto – titled “The beginnings of the social economy in Portugal: Contributions of Ramón de la Sagra”¹ – served as a motto for a tertulia hosted by the bookstore / cultural association Gato Vadio and the Institute of Sociology of the University of Porto as part of a “cycle of reflections on alternative socio-economic practices”.

Passing-by the city of Porto, the Catalan scholar fulfilled his will to “restore research to the people – an obligation of researchers”, presenting and discussing his work in a relaxed and informal environment. The session was also attended by Professor and historian Gaspar Pereira and representatives of three centennial institutions of Porto: Cooperativa do Povo Portuense (founded in 1900), the mutual reliefs association Associação de Socorros Mútuos – Beneficência Familiar (1877), and the league of mutual associations, Liga das Associações de Socorro Mútuo do Porto (1905). A room filled with curious people about the beginnings of the social economy in Portugal composed the environment for the lively debate that followed.

“At the basis of the social economy in Portugal are the mutual aid societies,” Jordi explains, situating the period of history upon which his work lies. “Cooperativism only came later, in the 1860s.”

His reflection then developed around the six topics I summarize below (the full audio of Estivill’s speech is available in Portuguese at the bottom of this post).

1. In 1840, Porto was already echoing Latin Europe publications on Social Economy

Estivill’s research began with the discovery of the publication of two chapters of the Treaty of Social Economy, by the Spanish sociologist and economist Ramon de la Sagra, in a Porto magazine in 1840 – Revista Litteraria. The dissemination of this treaty (which resulted from a series of lessons from the Sagra in the Athenaeum of Madrid) reveals that in Porto there was already sensitivity to these issues as early as 1840, which contradicts what Jordi points out as “the attempt of monopoly by the French, who argue that the introduction of the term social economy is theirs”, since 1838. “Oporto already echoed what was published on the other side. (…) Interesting to discover that the notion of social economy is not French heritage but at least of Latin Europe.”

2. The publications of the time on social economy mainly addressed a critique to the dominant political economy; critique to the welfare system and concerns with the fight against poverty; and proposals for social reform based on associationism and work.

(a) “social economy had to be different from political economy”: while the mainstream political economy of the time “was the science of the rich and classical economists,” the social economy, as an alternative, “had to be linked to the distribution, to the People – how the wealth that was produced had to be distributed by the People.”

(b) The history of the social economy in Portugal is closely linked to the struggle against poverty and to criticism of the country’s public and private welfare systems.

(c) the authors spoke of proposals for social reform around the creation of new forms of association and of giving value to work.

3. Between 1840 and 1870, different ideological and cultural families expressed themselves in various publications on social economy, composing what can be considered a school of thought in Portugal, including academics, workers, socialists, republicans, anarchists, jurists and economists, Catholic thinkers, liberals…

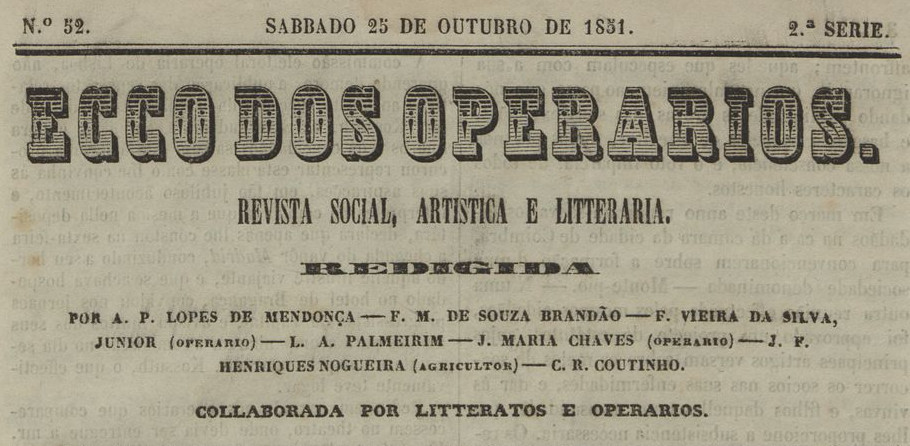

The notion of social economy was partly expressed by the Portuguese labor movement through the many magazines that existed at the time, such as “O Jornal do Operário”, “A Voz do Operário” and “Ecco dos Operários“. Citing the latter, Jordi highlights concerns about the “public interest”, the creation of an alternative to the English system, and the will to transform reality:

the English economic school occupies the written press, but we are going to give it a new fashion, new economic ideas to transform the real world into a legitimate research of and in the public interest (in Ecco dos Operários)

4. “The notion of social economy is very present in the early Iberian relations of that time.”

In 1870 the Workers’ Congress of Catalonia addressed a manifesto to the Portuguese workers, “to encourage them to associate themselves and enter into this perspective of the social economy.” Even earlier, in 1859, Sixto Cámara in the book A União Ibérica, “cites the social economy as element in his vision for an Iberian confederation.”

5. It is not possible to analyze the origins of the social economy in Portugal without taking into account “the informal economy, submerged labor, crafts work, mutual aid systems for agricultural and health work, artisanal production and participation in what we would now call the commons.”

Jordi mentions examples of mutual aid in the Trás os Montes region at the beginning of the 20th century, for the agricultural works and the joint manufacture of tiles; and also an article by Pereira on the Basic Law of 1867, which analyzes the 851 societies created in Portugal, and concludes that 50% were activated by members of artisan groups – “artisans were very present in the development of this type of societies.”

6. The polyvalence of the organizations was dominant, with concurring lines from the cooperative, mutualist and associativist movements.

“The associative movement was pre-syndicalist, it was a little bit cooperative, it was mutualistic of mutual aid and it was dedicated to the main necessities of the people of that time. It surprised the French that this polyvalence lasted for so long in Catalonia, Portugal and Italy.”

Finally, interclassism.

Refraining being too affirmative, Jordi questioned “to what extent these organizations were an expression of the working class, the artisans, a petty bourgeoisie, an ideological confluence of those who were against the absolutist system and in favor of a freer system?”

“There were workers who called themselves poets. In the workers’ magazines of that time there were literary expressions, and workers who wrote. I found references in Porto’s case, which showed that the gentlemen in the taverns or in some neighborhood restaurants held gatherings like this where it was possible to think that there was surely a relative interclassism, that they would agree, discuss, talk among themselves and share ideas, and they were also likely to share this idea of a liberating social economy.”

Listen to the intervention of Jordi Estivill (in Portuguese), with an introductory note by Cristina Parente and Sara Moreira:

[inserir audio]¹ ESTIVILL, Jordi (2017), “Os primórdios da economia social em Portugal. Contributos de Ramón de la Sagra – I Parte”, Sociologia: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Vol. XXXIII, pp. 19 – 45. DOI: 10.21747/08723419/soc33a2 ESTIVILL, Jordi (2017), “Os primórdios da economia social em Portugal. Contributos de Ramón de la Sagra (II Parte)”, Sociologia: Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Vol. XXXIV, pp. 11 - 26 DOI: 10.21747/08723419/soc34a1